Taekwondo

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A taekwondo match at the 2020 Summer Olympics | |

| Also known as | TKD, tae kwon do, tae kwon-do, taekwon-do, tae-kwon-do |

|---|---|

| Focus | Striking, kicking |

| Country of origin | South Korea |

| Creator | No single creator; a collaborative effort by representatives from the original nine Kwans, initially supervised by Choi Hong-hi.[1] |

| Famous practitioners | (see notable practitioners) |

| Parenthood | Mainly taekkyon and karate,[a] some Chinese martial arts[citation needed] |

| Olympic sport | Since 2000 (World Taekwondo) (demonstration sport in 1988) |

| |

| Highest governing body | World Taekwondo (South Korea) |

|---|---|

| First played | Korea, |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Full-contact (WT), Light and medium-contact (ITF, ITC, ATKDA, GBTF, GTF, ATA, TI,TCUK, TAGB) |

| Mixed-sex | Yes |

| Type | Combat sport |

| Equipment | Hogu, headgear |

| Presence | |

| Country or region | Worldwide |

| Olympic | Since 2000 |

| Paralympic | Since 2020 |

| World Games | 1981–1993 |

| Taekwondo | |

| Hangul | 태권도 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | 跆拳道 |

| Revised Romanization | taegwondo |

| McCune–Reischauer | t'aekwŏndo |

| IPA | [t̪ʰɛ.k͈wʌ̹n.d̪o] ⓘ |

Taekwondo (/ˌtaɪkwɒnˈdoʊ, ˌtaɪˈkwɒndoʊ, ˌtɛkwənˈdoʊ/; Korean: 태권도; [t̪ʰɛ.k͈wʌ̹n.d̪o] ⓘ) is a Korean martial art and combat sport involving punching and kicking techniques.[2][3][4] "Taekwondo" can be translated as tae ("strike with foot"), kwon ("strike with hand"), and do ("the art or way"). In addition to its five tenets of courtesy, integrity, perseverance, self-control and indomitable spirit, the sport requires three physical skills: poomsae (품새), kyorugi (겨루기) and gyeokpa (격파).

Poomsae are patterns that demonstrate a range of kicking, punching and blocking techniques, kyorugi involves the kind of sparring seen in the Olympics, and gyeokpa is the art of breaking wooden boards. Taekwondo also sometimes involves the use of weapons such as swords and nun-chucks. Taekwondo practitioners wear a uniform known as a dobok.

It is a combat sport which was developed during the 1940s and 1950s by Korean martial artists with experience in martial arts such as karate and Chinese martial arts.[5][6]

The oldest governing body for taekwondo is the Korea Taekwondo Association (KTA), formed in 1959 through a collaborative effort by representatives from the nine original kwans, or martial arts schools, in Korea. The main international organizational bodies for taekwondo today are various branches of the International Taekwon-Do Federation (ITF), originally founded by Choi Hong-hi in 1966, and the partnership of the Kukkiwon and World Taekwondo (WT, formerly World Taekwondo Federation or WTF), founded in 1972 and 1973 respectively by the Korea Taekwondo Association.[7] Gyeorugi ([kjʌɾuɡi]), a type of full-contact sparring, has been an Olympic event since 2000. In 2018, the South Korean government officially designated taekwondo as Korea's national martial art.[8] At the Olympic and Paralympic level, taekwondo is governed by World Taekwondo.[9]

History

[edit]Emergence of various kwans

[edit]Beginning in 1945, shortly after the end of World War II and the Japanese occupation, new martial arts schools called kwans opened in Seoul. These schools were established by Korean martial artists with backgrounds in Japanese[10] and Chinese martial arts.

Early progenitors of taekwondo—the founders of the nine original kwans—who were able to study in Japan were exposed to Japanese martial arts, including karate, judo, and kendo,[11] while others were exposed to the martial arts of China and Manchuria.[6][12][13]

Discussions around the historical influences of taekwondo have been controversial, with two main schools of thought: traditionalism and revisionism. Traditionalism holds that the origins of taekwondo are indigenous while revisionism, the prevailing theory, argues that taekwondo is rooted in karate.[14] In later years, the Korean government has been a significant supporter of traditionalist views as to divorce taekwondo from its link to Japan and give Korea a "legitimate cultural past".[15]

Attempt to standardise taekwondo

[edit]In 1952, South Korean president Syngman Rhee witnessed a martial arts demonstration by South Korean Army officers Choi Hong-hi and Nam Tae-hi from the 29th Infantry Division. He misrecognized the technique on display as taekkyon,[16][page needed][17][18] and urged martial arts to be introduced to the army under a single system. Beginning in 1955 the leaders of the kwans began discussing in earnest the possibility of creating a unified Korean martial art. Until then, "Tang Soo Do" was the term used for Korean karate, using the Korean hanja pronunciation of the Japanese kanji 唐手道. The name "Tae Soo Do" (跆手道) was also used to describe a unified style Korean martial arts. This name consists of the hanja 跆 tae "to stomp, trample", 手 su "hand" and 道 do "way, discipline".[citation needed]

Choi Hong-hi advocated the use of the name "Tae Kwon Do", replacing su "hand" with 拳 kwon (Revised Romanization: gwon; McCune–Reischauer: kwŏn) "fist", the term also used for "martial arts" in Chinese (pinyin quán).[19] The name was also the closest to the pronunciation of "taekkyon",[20][16][page needed][21] The new name was initially slow to catch on among the leaders of the kwans. During this time taekwondo was also adopted for use by the South Korean military, which increased its popularity among civilian martial arts schools.[7][page needed][16][page needed]

Development of multiple styles

[edit]In 1959, the Korea Tang Soo Do Association (later Korea Taekwondo Association or KTA) was established to facilitate the unification of Korean martial arts. Choi wanted all the other member kwans of the KTA to adopt his own Chan Hon-style of taekwondo, as a unified style. This was, however, met with resistance as the other kwans instead wanted a unified style to be created based on inputs from all the kwans, to serve as a way to bring on the heritage and characteristics of all of the styles, not just the style of a single kwan.[7][page needed] As a response to this, along with political disagreements about teaching taekwondo in North Korea and unifying the whole Korean Peninsula, Choi broke with the (South Korea) KTA in 1966, in order to establish the International Taekwon-Do Federation (ITF)— a separate governing body devoted to institutionalizing his Chan Hon-style of taekwondo in Canada.[7][page needed][16]

Initially, the South Korean president gave Choi's ITF limited support, due to their personal relationship.[7][page needed] However, Choi and the government later split on the issue of whether to accept North Korean influence on the martial art. In 1972, South Korea withdrew its support for the ITF. The ITF continued to function as an independent federation, then headquartered in Toronto, Canada. Choi continued to develop the ITF-style, notably with the 1983 publication of his Encyclopedia of Taekwon-Do. After his retirement, the ITF split in 2001 and then again in 2002 to create three separate ITF federations, each of which continues to operate today under the same name.[7][page needed]

In 1972, the KTA and the South Korean government's Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism established the Kukkiwon as the new national academy for taekwondo. Kukkiwon now serves many of the functions previously served by the KTA, in terms of defining a government-sponsored unified style of taekwondo. In 1973 the KTA and Kukkiwon supported the establishment of the World Taekwondo Federation (WTF), which later changed its name to "World Taekwondo" (WT) in 2017 due to the previous initialism overlapping with an internet slang term.[22] While the Kukkiwon focus on the martial art and self-defence aspects of Kukki-Taekwondo, the WT promoted the sportive side, and its competitions employ a subset of the techniqes present in the Kukkiwon-style taekwondo.[7][page needed][23] For this reason, Kukkiwon-style Taekwondo is often referred to as WT-style Taekwondo, sport-style Taekwondo, or Olympic-style Taekwondo, though in reality the style is defined by the Kukkiwon, not the WT.[citation needed]

Since 2000, taekwondo has been one of three Asian martial arts (the others being judo and karate), and one of six total (the others being the previously mentioned, Greco-Roman wrestling, freestyle wrestling, and boxing) included in the Olympic Games. It started as a demonstration event at the 1988 games in Seoul, a year after becoming a medal event at the Pan Am Games, and became an official medal event at the 2000 games in Sydney. In 2010, taekwondo was accepted as a Commonwealth Games sport.[24]

Features

[edit]

Taekwondo is characterized by its emphasis on head-height kicks, jumping and spinning kicks, and fast kicking techniques. In fact, WT sparring competitions award additional points for strikes that incorporate spinning kicks, kicks to the head, or both.[25]

Typical curriculum

[edit]

While organisations such as ITF or Kukkiwon define the general style of taekwondo, individual clubs and schools tend to tailor their taekwondo practices. Although each taekwondo club or school is different, a student typically takes part in most or all of the following:[26]

- Forms (품새; pumsae or poomsae, also 형; 型; hyeong; hyung, and 틀; teul; tul): these serve the same function as kata in the study of karate

- Sparring (겨루기; gyeorugi or 맞서기; matseogi): sparring includes variations such as freestyle sparring (in which competitors spar without interruption for several minutes); seven-, three-, two-, and one-step sparring (in which students practice pre-arranged sparring combinations); and point sparring (in which sparring is interrupted and then resumed after each point is scored)

- Breaking (격파; 擊破; gyeokpa or weerok): the breaking of boards is used for testing, training, and martial arts demonstrations. Demonstrations often also incorporate bricks, tiles, and blocks of ice or other materials. These techniques can be separated into three types:

- Power breaking – using straightforward techniques to break as many boards as possible

- Speed breaking – boards are held loosely by one edge, putting special focus on the speed required to perform the break

- Special techniques – breaking fewer boards but by using jumping or flying techniques to attain greater height, distance, or to clear obstacles

- Self-defense techniques (호신술; 護身術; hosinsul)

- Throwing and/or falling techniques (던지기; deonjigi or tteoreojigi 떨어지기)

- Both anaerobic and aerobic workout, including stretching

- Relaxation and meditation exercises, as well as breathing control

- A focus on mental and ethical discipline, etiquette, justice, respect, self-confidence, and leadership skills

- Examinations to progress to the next rank

Though weapons training is not a formal part of most taekwondo federation curriculum, individual schools will often incorporate additional training with weapons such as staffs, knives, and sticks.

Styles and organizations

[edit]There are a number of major taekwondo styles as well as a few niche styles. Most styles are associated with a governing body or federation that defines the style.[27] The major technical differences among taekwondo styles and organizations generally revolve around:

- The patterns practiced by each style (called 형; hyeong, pumsae 품새, or tul 틀, depending on the style); these are sets of prescribed formal sequences of movements that demonstrate mastery of posture, positioning, and technique

- Differences in the sparring rules for competition.

- Martial arts philosophy.

1946: Traditional Taekwondo

[edit]"Traditional Taekwondo" refers to the 1940s and 1950s martial arts by the nine original kwans. They used a number of different names such as Tang Soo Do (Chinese Hand Way),[b] Kong Soo Do (Empty Hand Way)[c] and Tae Soo Do (Foot Hand Way).[d] Traditional Taekwondo is still practised today but generally under names like Tang Soo Do and Soo Bahk Do.[7][16] In 1959, the name taekwondo was agreed upon by the nine original kwans as a common term for their martial arts. As part of the unification process, The Korea Taekwondo Association (KTA) was formed through a collaborative effort by representatives from all the kwans, and the work began on a common curriculum, which eventually resulted in the Kukkiwon and the Kukki Style of Taekwondo. The original kwans that formed KTA continues to exist today, but as independent fraternal membership organizations that support the World Taekwondo and Kukkiwon. The kwans also function as a channel for the issuing of Kukkiwon dan and poom certification (black belt ranks) for their members. The official curriculum of those kwans that joined the unification is that of the Kukkiwon, with the notable exception of half the Oh Do Kwan which joined the ITF instead and therefore uses the Chan Hon curriculum.[citation needed]

1966: ITF/Chang Hon-style Taekwondo

[edit]International Taekwon-Do Federation (ITF)-style Taekwondo, more accurately known as Chang Hon-style Taekwondo, is defined by Choi Hong-hi's Encyclopedia of Taekwon-Do published in 1983.[28]

In 1990, the Global Taekwondo Federation (GTF) split from the ITF due to the political controversies surrounding the ITF; the GTF continues to practice ITF-style Taekwondo, however, with additional elements incorporated into the style. Likewise, the ITF itself split in 2001 and again in 2002 into three separate federations, headquartered in Austria, the United Kingdom, and Spain respectively.[29][30][31]

The GTF and all three ITFs practice Choi's ITF-style Taekwondo. In ITF-style Taekwondo, the word used for "forms" is tul; the specific set of tul used by the ITF is called Chang Hon. Choi defined 24 Chang Hon tul. The names and symbolism of the Chang Hon tul refer to elements of Korean history, culture and religious philosophy. The GTF-variant of ITF practices an additional six tul.[citation needed]

Within the ITF taekwondo tradition there are two sub-styles:

- The style of taekwondo practised by the ITF before its 1973 split with the KTA is sometimes called by ITF practitioners "Traditional Taekwondo", though a more accurate term would be Traditional ITF Taekwondo.

- After the 1973 split, Choi Hong-hi continued to develop and refine the style, ultimately publishing his work in his 1983 Encyclopedia of Taekwondo. Among the refinements incorporated into this new sub-style is the "sine wave"; one of Choi Hong-hi's later principles of taekwondo is that the body's centre of gravity should be raised-and-lowered throughout a movement.

Some ITF schools adopt the sine wave style, while others do not. Essentially all ITF schools do, however, use the patterns (tul) defined in the Encyclopedia, with some exceptions related to the forms Juche and Ko-Dang.[citation needed]

1969: ATA/Songahm-style Taekwondo

[edit]In 1969, Haeng Ung Lee, a former Taekwondo instructor in the South Korean military, relocated to Omaha, Nebraska and established a chain of martial arts schools in the United States under the banner of the American Taekwondo Association (ATA). Like Jhoon Rhee Taekwondo, ATA Taekwondo has its roots in traditional taekwondo. The style of Taekwondo practised by the ATA is called Songahm Taekwondo. The ATA went on to become one of the largest chains of Taekwondo schools in the United States.[32]

The ATA established international spin-offs called the Songahm Taekwondo Federation (STF) and the World Traditional Taekwondo Union (WTTU) to promote the practice of Songahm Taekwondo internationally. In 2015, all the spin-offs were reunited under the umbrella of ATA International.[citation needed]

1970s: Jhoon Rhee-style Taekwondo

[edit]In 1962 Jhoon Rhee, upon graduating from college in Texas, relocated to and established a chain of martial arts schools in the Washington, D.C. area that practiced Traditional Taekwondo.[e] In the 1970s, at the urging of Choi Hong-hi, Rhee adopted ITF-style Taekwondo within his chain of schools, but like the GTF later departed from the ITF due to the political controversies surrounding Choi and the ITF. Rhee went on to develop his own style of taekwondo called Jhoon Rhee-style Taekwondo, incorporating elements of both traditional and ITF-style Taekwondo as well as original elements.[33]

1972: Kukki-style / WT-Taekwondo

[edit]

In 1972 the Korea Taekwondo Association (KTA) Central Dojang opened in Seoul; in 1973 the name was changed to Kukkiwon. Under the sponsorship of the South Korean government's Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism the Kukkiwon became the new national academy for Taekwondo, thereby establishing a new "unified" style of Taekwondo.[23] In 1973 the KTA established the World Taekwondo Federation (WTF, now called World Taekwondo, WT) to promote the sportive side of Kukki-Taekwondo. The International Olympic Committee recognized the WT and Taekwondo sparring in 1980. For this reason, the Kukkiwon-defined style of Taekwondo is sometimes referred to as Sport-style Taekwondo, Olympic-style Taekwondo, or WT-style Taekwondo, but the style itself is defined by the Kukkiwon, not by the WT, and the WT competition ruleset itself only allows the use of a very small number of the total number of techniques included in the style.[34]

Extreme Taekwondo

[edit]Extreme Taekwondo is a hybrid style created in 2008, by Taekwondo practitioner Shin-Min Cheol, who also founded Mirme Korea in 2012, a production company that helped spreading his style. His company is based on promoting TKD tournaments, in a style which mixed other martial arts like Karate and Capoeira.[35]

Hup Kwon Do

[edit]Hup Kwon Do is a hybrid style of Taekwondo created by a Malayan martial artist called Grandmaster Lee in 1989. He opened his first school in Penang, and originally developed this system as a self-defense technique, mixing Taekwondo with a multitude of other martial arts, such as Kendo, Bokken, Wado Shimpo, Kickboxing and Karate. It is mainly governed by the World Hupkwondo Council (WHC).[36][37]

Han Moo Do

[edit]Han Moo Doo is a hybrid martial art created by Korean practitioner Yoon Sung Hwang in 1989, in Kauhava, Finland. Like other variations of Taekwondo, it first started out as a method of self-defense before spreading across Northern countries such as Sweden, Norway and Denmark. It combines Taekwondo with other Korean martial arts like Hapkido and Hoi Jeon Moo Sool. It mixes striking and grappling techniques, and some schools also incorporate weapons training into it.[38][39]

Han Mu Do

[edit]Han Mu Do is a martial art developed by Korean practitioner Dr. Young Kimm, who founded the World Hanmudo Association to assure the preservation of his style. Its ideals are mostly based on the Han philosophy, mainly about the mind balance of the practitioner. Young Kimm studied Taekwondo, Tang Soo Do, Kuk Sul, Hapkido, Korean Judo and Kum Do, mixing all of their techniques together to create his own style.[40][41]

Teuk Gong Moo Sool

[edit]Teukgong Moosool is a combat system developed in South Korea by the special forces units that is projected to stop the opponent as quickly as possible, although it was also used in sports competition. It is a hybrid style that mixes Taekwondo, Judo, Hapkido, Sanda (and other Chinese wushu styles) and Korean Kickboxing and it follows the Yin-Yang and five elements philosophy. Its origins date back to the 1960s–70s, but it was only introduced in special forces training in 1979.[42][43]

Hoshin Moosool

[edit]Hoshin Moosool is a martial art and combat system founded by Taekwondo Grandmaster Kwan-Young Lee. Its techniques and method are inspired from Master Lee's experience as a close combat instructor during the Vietnam war, instructor for the French Police Elite Unit (RAID) and time as a member of the Korean and French intelligence service.[citation needed]

Equipment and facilities

[edit]

A Taekwondo practitioner typically wears a dobok (도복; 道服) uniform with a belt tied around the waist.

When sparring, padded equipment is usually worn. In the ITF tradition, typically only the hands and feet are padded. In the Kukkiwon/WT tradition, full-contact sparring is facilitated by the employment of more extensive equipment: padded helmets called homyun are always worn, as are padded torso protectors called hogu; feet, shins, groins, hands, and forearms protectors are also worn.[citation needed]

The school or place where instruction is given is called a dojang (도장; 道場).

Ranks, belts, and promotion

[edit]

Taekwondo ranks vary from style to style and are not standardized. For junior ranks, ranks are indicated by a number and the term (급; 級; geup, gup, or kup), which represents belt color. A belt color may have a stripe in it. Ranks typically count down from higher numbers to lower ones. For senior ranks ("black belt" ranks), each rank is called a dan 단 (段) or "degree" and counts upwards.[44]

Students must pass tests to advance ranks, and promotions happen at a progressive rate depending on the school.[citation needed]

Titles can also come with ranks. For example, in the International Taekwon-Do Federation, instructors holding 1st to 3rd dan are called boosabum (부사범; 副師範; "assistant instructor"), those holding 4th to 6th dan are called sabum (사범; 師範; "instructor"), those holding 7th to 8th dan are called sahyun (사현; 師賢; "master"), and those holding 9th dan are called saseong (사성; 師聖; "grandmaster").[45]

In WT/Kukki-Taekwondo, instructors holding 1st. to 3rd. dan are considered assistant instructors (kyosa-nim), are not yet allowed to issue ranks, and are generally thought of as still having much to learn. Instructors who hold a 4th. to 6th. dan are considered master instructors (sabum-nim), and are allowed to grade students to ranks beneath their own. Rules of Taekwondo Promotion Test, Kukkiwon Those who hold a 7th–9th dan are considered Grandmasters. Kukkiwon-issued ranks also hold an age requirement, with grandmaster ranks requiring an age of over forty.[46]

Forms (patterns)

[edit]

Three Korean terms may be used with reference to taekwondo forms or patterns. These forms are equivalent to kata in karate.

- Hyeong (sometimes hyung; 형; 形) is the term usually used in Traditional Taekwondo (i.e., 1950s–1960s styles of Korean martial arts).

- Poomsae (sometimes pumsae or formerly poomse; 품새; 品勢) is the term officially used by Kukkiwon/WT-style and ATA-style Taekwondo.

- Teul (officially romanized as tul; 틀) is the term usually used in ITF/Chang Hon-style Taekwondo.

A hyeong is a systematic, prearranged sequence of martial techniques that is performed either with or without the use of a weapon.[citation needed]

Different taekwondo styles and associations (ATA, ITF, GTF, WT, etc.) use different taekwondo forms.[citation needed]

Philosophy

[edit]Different styles of Taekwondo adopt different philosophical underpinnings. Many of these underpinnings however refer back to the Five Commandments of the Hwarang as a historical referent. For example, Choi Hong-hi expressed his philosophical basis for taekwondo as the Five Tenets of Taekwondo:[47]

- Courtesy (예의; 禮儀; yeui)

- Integrity (염치; 廉恥; yeomchi)

- Perseverance (인내; 忍耐; innae)

- Self-control (극기; 克己; geukgi)

- Indomitable spirit (백절불굴; 百折不屈; baekjeolbulgul)

These tenets are further articulated in a taekwondo oath, also authored by Choi:

- I shall observe the tenets of taekwondo

- I shall respect the instructor and seniors

- I shall never misuse taekwondo

- I shall be a champion of freedom and justice

- I shall build a more peaceful world

Modern ITF organizations have continued to update and expand upon this philosophy.[48][49]

The World Taekwondo Federation (WTF) also refers to the commandments of the Hwarang in the articulation of its taekwondo philosophy.[50] Like the ITF philosophy, it centers on the development of a peaceful society as one of the overarching goals for the practice of taekwondo. The WT's stated philosophy is that this goal can be furthered by adoption of the Hwarang spirit, by behaving rationally ("education in accordance with the reason of heaven"), and by recognition of the philosophies embodied in the taegeuk (the yin and the yang, i.e., "the unity of opposites") and the sam taegeuk (understanding change in the world as the interactions of the heavens, the Earth, and Man). The philosophical position articulated by the Kukkiwon is likewise based on the Hwarang tradition.[51]

Theory of power

[edit]The emphasis on speed and agility is a defining characteristic of taekwondo and has its origins in analyses undertaken by Choi Hong-hi. The results of that analysis are known by ITF practitioners as Choi's Theory of Power. Choi based his understanding of power on biomechanics and Newtonian physics as well as Chinese martial arts. For example, Choi observed that the kinetic energy of a strike increases quadratically with the speed of the strike, but increases only linearly with the mass of the striking object. In other words, speed is more important than size in terms of generating power. This principle was incorporated into the early design of taekwondo and is still used.[16][28]

Choi also advocated a "relax/strike" principle for taekwondo; in other words, between blocks, kicks, and strikes the practitioner should relax the body, then tense the muscles only while performing the technique. It is believed that the relax/strike principle increases the power of the technique, by conserving the body's energy. He expanded on this principle with his advocacy of the "sine wave" technique. This involves raising one's centre of gravity between techniques, then lowering it as the technique is performed, producing the up-and-down movement from which the term "sine wave" is derived.[28]

The components of the Theory of Power include:[52]

- Reaction Force: the principle that as the striking limb is brought forward, other parts of the body should be brought backwards in order to provide more power to the striking limb. As an example, if the right leg is brought forward in a roundhouse kick, the right arm is brought backwards to provide the reaction force.

- Concentration: the principle of bringing as many muscles as possible to bear on a strike, concentrating the area of impact into as small an area as possible.

- Equilibrium: maintaining a correct centre-of-balance throughout a technique.

- Breath Control: the idea that during a strike one should exhale, with the exhalation concluding at the moment of impact.

- Mass: the principle of bringing as much of the body to bear on a strike as possible; again using the turning kick as an example, the idea would be to rotate the hip as well as the leg during the kick in order to take advantage of the hip's additional mass in terms of providing power to the kick.

- Speed: as previously noted, the speed of execution of a technique in taekwondo is deemed to be even more important than mass in terms of providing power.

Competitions

[edit]

Taekwondo competitions typically involve sparring, breaking, and patterns; some tournaments also include special events such as demonstration teams and self-defense (hosinsul). In Olympic taekwondo competitions, however, only sparring (using WT competition rules) is performed.[53]

There are two kinds of competition sparring: point sparring, in which all strikes are light contact and the clock is stopped when a point is scored; and Olympic sparring, where all strikes are full contact and the clock continues when points are scored.[citation needed]

World Taekwondo

[edit]

Under World Taekwondo (WT, formerly WTF) and Olympic rules, sparring is a full-contact event, employing a continuous scoring system where the fighters are allowed to continue after scoring each technique, taking place between two competitors in either an area measuring 8 meters square or an octagon of similar size.[54] Competitors are matched within gender and weight division—eight divisions for World Championships that are condensed to four for the Olympics. A win can occur by points, or if one competitor is unable to continue (knockout). However, there are several decisions that can lead to a win, as well, including superiority, withdrawal, disqualification, or even a referee's punitive declaration.[55] Each match consists of three two-minute rounds, with one minute rest between rounds, though these are often abbreviated or shortened for some junior and regional tournaments.[54] Competitors must wear a hogu, head protector, shin pads, foot socks, forearm guards, hand gloves, a mouthpiece, and a groin cup. Tournaments sanctioned by national governing bodies or the WT, including the Olympics and World Championship, use electronic hogus, electronic foot socks, and electronic head protectors to register and determine scoring techniques, with human judges used to assess and score technical (spinning) techniques and score punches.[54]

Points are awarded for permitted techniques delivered to the legal scoring areas as determined by an electronic scoring system, which assesses the strength and location of the contact. The only techniques allowed are kicks (delivering a strike using an area of the foot below the ankle), punches (delivering a strike using the closed fist), and pushes. In some smaller tournaments, and in the past, points were awarded by three corner judges using electronic scoring tallies. All major national and international tournaments have moved fully (as of 2017) to electronic scoring, including the use of electronic headgear. This limits corner judges to scoring only technical points and punches. Some believe that the new electronic scoring system reduces controversy concerning judging decisions,[56] but this technology is still not universally accepted.[57] In particular, the move to electronic headgear has replaced controversy over judging with controversy over how the technology has changed the sport. Because the headgear is not able to determine if a kick was a correct taekwondo technique, and the pressure threshold for sensor activation for headgear is kept low for safety reasons, athletes who improvised ways of placing their foot on their opponents head were able to score points, regardless of how true to taekwondo those techniques were.[58]

Techniques are divided into three categories: scoring techniques (such as a kick to the hogu), permitted but non-scoring techniques (such as a kick that strikes an arm), and not-permitted techniques (such as a kick below the waist).

- A punch that makes strong contact with the opponent's hogu scores 1 point. The punch must be a straight punch with arm extended; jabs, hooks, uppercuts, etc. are permitted but do not score. Punches to the head are not allowed.

- A regular kick (no turning or spinning) to the hogu scores 2 points.

- A regular kick (no turning or spinning) to the head scores 3 points

- A technical kick (a kick that involves turning or spinning) to the hogu scores 4 points.

- A technical kick to the head scores 5 points.

- As of October 2010, 4 points were awarded if a turning kick was used to execute this attack. As of June 2018, this was changed to 5 points.[59]

The referee can give penalties at any time for rule-breaking, such as hitting an area not recognized as a target, usually the legs or neck. Penalties, called "Gam-jeom" are counted as an addition of one point for the opposing contestant. Following 10 "Gam-jeom" a player is declared the loser by referee's punitive declaration[54]

At the end of three rounds, the competitor with most points wins the match. In the event of a tie, a fourth "sudden death" overtime round, sometimes called a "Golden Point", is held to determine the winner after a one-minute rest period. In this round, the first competitor to score a point wins the match. If there is no score in the additional round, the winner is decided by superiority, as determined by the refereeing officials[59] or number of fouls committed during that round. If a competitor has a 20-point lead at the end of the second round or achieves a 20-point lead at any point in the third round, then the match is over and that competitor is declared the winner.[54]

In addition to sparring competition, World Taekwondo sanctions competition in poomsae or forms, although this is not an Olympic event. Single competitors perform a designated pattern of movements, and are assessed by judges for accuracy (accuracy of movements, balance, precision of details) and presentation (speed and power, rhythm, energy), both of which receive numerical scores, with deductions made for errors.[60] Pair and team competition is also recognized, where two or more competitors perform the same form at the same time. In addition to competition with the traditional forms, there is experimentation with freestyle forms that allow more creativity.[60]

International Taekwon-Do Federation

[edit]

The International Taekwon-Do Federation (ITF) has sparring rules similar to the WT's, but they differ in some ways:

- Hand attacks to the head are allowed.[61]

- The competition is not full contact, and excessive contact is not allowed.

- Competitors are penalized with disqualification if they injure their opponent and he can no longer continue (knockout).

- The scoring system is:

- 1 point for Punch to the body or head.

- 2 points for Jumping kick to the body or kick to the head, or a jumping punch to the head

- 3 points for Jumping kick to the head

- The competition area is 9×9 meters for international events.

Competitors do not wear the hogu (although they are required to wear approved foot and hand protection equipment, as well as optional head guards). This scoring system varies between individual organisations within the ITF; for example, in the TAGB, punches to the head or body score 1 point, kicks to the body score 2 points, and kicks to the head score 3 points.

A continuous point system is utilized in ITF competition, where the fighters are allowed to continue after scoring a technique. Excessive contact is generally not allowed according to the official ruleset, and judges penalize any competitor with disqualification if they injure their opponent and he can no longer continue (although these rules vary between ITF organizations). At the end of two minutes (or some other specified time), the competitor with more scoring techniques wins.

Fouls in ITF sparring include: attacking a fallen opponent, leg sweeping, holding/grabbing, or intentional attack to a target other than the opponent.[62]

ITF competitions also feature performances of patterns, breaking, and 'special techniques' (where competitors perform prescribed board breaks at great heights).

Multi-discipline competition

[edit]Some organizations deliver multi-discipline competitions, for example the British Student Taekwondo Federation's inter-university competitions, which have included separate WT rules sparring, ITF rules sparring, Kukkiwon patterns and Chang-Hon patterns events run in parallel since 1992.[63]

Other organizations

[edit]American Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) competitions are very similar, except that different styles of pads and gear are allowed.[64]

List of competitions

[edit]World Taekwondo competitions

[edit]World Taekwondo (WT) directly sanctions the following competitions:[65]

- World Taekwondo Poomsae Championships

- World Taekwondo Championships

- World Para Taekwondo Championships (since 2009)[66]

- World Taekwondo Cadet Championships

- World Taekwondo Junior Championships

- World Taekwondo Team Championships

- World Taekwondo Para Championships

- World Taekwondo Grand Prix

- World Taekwondo Grand Slam

- World Taekwondo Beach Championships

- Olympic Games

- Paralympic Games (debut in 2020 Tokyo Paralympics)[67]

Other tournaments

[edit]These feature WT Taekwondo only:[citation needed]

Taekwondo is also an optional sport at the Commonwealth Games.[citation needed]

Weight divisions

[edit]The following weight divisions are in effect due to the WT[68] and ITF[69] tournament rules and regulations:

| Olympics | |

|---|---|

Male |

Female

|

| −58 kg | −49 kg |

| −68 kg | −57 kg |

| −80 kg | −67 kg |

| +80 kg | +67 kg |

| WT Male Championships | |

|---|---|

Juniors |

Adults

|

| −45 kg | −54 kg |

| −48 kg | |

| −51 kg | |

| −55 kg | |

| −59 kg | −58 kg |

| −63 kg | −63 kg |

| −68 kg | −68 kg |

| −73 kg | −74 kg |

| −78 kg | |

| +78 kg | −80 kg |

| −87 kg | |

| +87 kg | |

| WT Female Championships | |

|---|---|

Juniors |

Adults

|

| −42 kg | −46 kg |

| −44 kg | |

| −46 kg | −49 kg |

| −49 kg | |

| −52 kg | −53 kg |

| −55 kg | |

| −59 kg | −57 kg |

| −63 kg | −62 kg |

| −68 kg | −67 kg |

| +68 kg | −73 kg |

| +73 kg | |

| ITF Male Championships | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Juniors |

Adults (18–39 yrs) |

Veterans over 40 |

Veterans over 50

|

| −45 kg | −50 kg | −64 kg | −66 kg |

| −51 kg | −57 kg | ||

| −57 kg | −64 kg | −73 kg | |

| −63 kg | −71 kg | ||

| −69 kg | −78 kg | −80 kg | −80 kg |

| −75 kg | −85 kg | −90 kg | |

| +75 kg | +85 kg | +90 kg | +80 kg |

| ITF Female Championships | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Juniors |

Adults (18–39 yrs) |

Veterans over 40 |

Veterans over 50

|

| −40 kg | −45 kg | −54 kg | −60 kg |

| −46 kg | −51 kg | ||

| −52 kg | −57 kg | −61 kg | |

| −58 kg | −63 kg | ||

| −64 kg | −69 kg | −68 kg | −75 kg |

| −70 kg | −75 kg | −75 kg | |

| +70 kg | +75 kg | +75 kg | +75 kg |

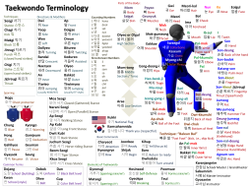

Taekwondo Korean terms

[edit]

In taekwondo schools—even outside Korea—Korean language commands and vocabulary are often used. Korean numerals may be used as prompts for commands or for counting repetition exercises. Different schools and associations will use different vocabulary, however, and may even refer to entirely different techniques by the same name. As one example, in Kukkiwon/WT-style Taekwondo, the term ap seogi refers to an upright walking stance, while in ITF/Chang Hon-style Taekwondo ap seogi refers to a long, low, front stance. Korean vocabulary commonly used in taekwondo schools includes:

| Basic Commands | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| English | Hangul | Hanja | Revised Romanization |

| Attention | 차렷 | Charyeot | |

| Ready | 준비 | 準備 | Junbi |

| Begin | 시작 | 始作 | Sijak |

| Finish / Stop | 그만 | Geuman | |

| Bow | 경례 | 敬禮 | Gyeonglye |

| Resume / Continue | 계속 | 繼續 | Gyesok |

| Return to ready | 바로 | Baro | |

| Relax / At ease | 쉬어 | Swieo | |

| Rest / Take a break | 휴식 | 休息 | Hyusik |

| Turn around / About face | 뒤로돌아 | Dwirodora | |

| Yell | 기합 | 氣合 | Gihap |

| Look / Focus | 시선 | 視線 | Siseon |

| By the count | 구령에 맞춰서 | 口令에 맞춰서 | Guryeong-e majchwoseo |

| Without count | 구령 없이 | 口令 없이 | Guryeong eobs-i |

| Switch feet | 발 바꿔 | Bal bakkwo | |

| Dismissed | 해산 | 解散 | Haesan |

| Hand Techniques | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| English | Hangul | Hanja | Revised Romanization |

| Hand Techniques | 수 기 | 手技 | Su gi |

| Attack / Strike / Hit | 공격 | 攻擊 | Gong-gyeog |

| Strike | 치기 | Chigi | |

| Block | 막기 | Magki | |

| Punch/hit | 권 | 拳 | Gwon |

| Punch | 지르기 | Jireugi | |

| Middle punch | 중 권 | 中拳 | Jung gwon |

| Middle Punch | 몸통 지르기 | Momtong jireugi | |

| Back fist | 갑 권 | 甲拳 / 角拳 | Gab gwon |

| Back fist | 등주먹 | Deungjumeog | |

| Knife hand (edge) | 수도 | 手刀 | Su Do |

| Knife hand (edge) | 손날 | Son Kal | |

| Thrust / spear | 관 | 貫 | Gwan |

| Thrust / spear | 찌르기 | Jjileugi | |

| Spear hand | 관 수 | 貫手 | Gwan su |

| Spear hand (lit. fingertip) | 손끝 | Sonkkeut | |

| Ridge hand | 역 수도 | 逆手刀 | Yeog su do |

| Ridge hand (lit. reverse hand blade) | 손날등 | Sonnaldeung | |

| Hammer fist | 권도 | 拳刀 / 拳槌 | Gweon do |

| Pliers hand | 집게 손 | Jibge son | |

| Palm heel | 장관 | 掌貫 | Jang gwan |

| Palm heel | 바탕손 | Batangson | |

| Elbow | 팔꿈 | Palkkum | |

| Gooseneck | 손목 등 | Sonmog deung | |

| Side punch | 횡진 공격 | 橫進攻擊 | Hoengjin gong gyeog |

| Side punch | 옆 지르기 | Yeop jileugi | |

| Mountain block | 산 막기 | 山막기 | San maggi |

| One finger fist | 일 지 권 | 一指拳 | il ji gwon |

| 1 finger spear hand | 일 지관 수 | 一指貫手 | il ji gwan su |

| 2 finger spear hand | 이지관수 | 二指貫手 | i ji gwan su |

| Double back fist | 장갑권 | 長甲拳 | Jang gab gwon |

| Double hammer fist | 장 권도 | 長拳刀 | Jang gwon do |

| Foot Techniques | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| English | Hangul | Hanja | Revised Romanization |

| Foot Techniques | 족기 | 足技 | Jog gi |

| Kick | 차기 | Chagi | |

| Front snap kick | 앞 차기 | Ap chagi | |

| ...also Front snap kick | 앞 차넣기 | Ap chaneohgi | |

| ...also Front snap kick | 앞 뻗어 차기 | Ap ppeod-eo chagi | |

| Inside-out heel kick or outside crescent kick | 안에서 밖으로 차기 | An-eseo bakk-eulo chagi | |

| Outside-in heel kick or inside crescent kick | 밖에서 안으로 차기 | Baggeso aneuro chagi | |

| Stretching front kick | 앞 뻗어 올리 기 | Ap ppeod-eo olli gi | |

| Roundhouse kick | 돌려 차기 | Dollyeo chagi | |

| ...also Roundhouse kick | Ap dollyeo chagi | ||

| Side kick | 옆 차기 | Yeop chagi | |

| ...also Snap Side kick | 옆 뻗어 차기 | Yeop ppeod-eo chagi | |

| Hook kick | 후려기 차기 | Hulyeogi chagi | |

| ...also hook kick | 후려 차기 | Huryeo chagi | |

| Back kick | 뒤 차기 | Dwi chagi | |

| ...also Spin Back kick | 뒤 돌려 차기 | Dwi dollyeo chagi | |

| Spin hook kick | 뒤 돌려 후려기 차기 | Dwi dollyeo hulyeogi chagi | |

| Knee strike | 무릎 차기 | Mu reup chagi | |

| Reverse round kick | 빗 차기 | Bit chagi | |

| Stances | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| English | Hangul (한글) | Hanja (한자/漢字) | Revised Romanization |

| Stances | 자세 | 姿勢 | Seogi (stance) or Jase (posture) |

| Ready stance | 준비 자세 | 準備 姿勢 | Junbi seogi (or jase) |

| Front Stance | 전굴 자세 | 前屈 姿勢 | Jeongul seogi (or jase) |

| Back Stance | 후굴 자세 | 後屈 姿勢 | Hugul seogi (or jase) |

| Horse-riding Stance | 기마 자세 | 騎馬 姿勢 | Gima seogi (or jase) |

| ...also Horse-riding Stance | 기마립 자세 | 騎馬立 姿勢 | Gimalip seogi (or jase) |

| ...also Horse-riding Stance | 주춤 서기 | Juchum seogi | |

| Side Stance | 사고립 자세 | 四股立 姿勢 | Sagolib seogi (or jase) |

| Cross legged stance | 교차 립 자세 | 交(叉/差)立 姿勢 | Gyocha lib seogi (or jase) |

| Technique Direction | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| English | Hangul | Hanja | Revised Romanization |

| Moving forward | 전진 | 推進 | Jeonjin |

| Backing up / retreat | 후진 | 後進 | Hujin |

| Sideways/laterally | 횡진 | 橫進 | Hoengjin |

| Reverse (hand/foot) | 역진 | 逆進 | Yeogjin |

| Lower | 하단 | 下段 | Hadan |

| Middle | 중단 | 中段 | Jungdan |

| Upper | 상단 | 上段 | Sangdan |

| Two handed | 쌍수 | 雙手 | Ssangsu |

| Both hands | 양수 | 兩手 | Yangsu |

| Lowest | 최 하단 | 最下段 | Choe hadan |

| Right side | 오른 쪽 | Oleun jjog | |

| Left side | 왼 쪽 | Oen jjog | |

| Other side/Twist | 틀어 | Teul-eo | |

| Inside-outside | 안에서 밖으로 | An-eseo bakk-eulo | |

| Outside inside | 밖에서 안으로 | Bakk-eseo an-eulo | |

| Jumping / 2nd level | 이단 | 二段 | Idan |

| Hopping / Skipping | 뜀을 | Ttwim-eul | |

| Double kick | 두 발 | Du bal | |

| Combo kick | 연속 | 連續 | Yeonsog |

| Same foot | 같은 발 | Gat-eun bal | |

| Titles | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| English | Hangul | Hanja | Revised Romanization |

| Founder/President | 관장 님 | 館長님 | Gwanjang nim |

| Master instructor | 사범 님 | 師範님 | Sabeom nim |

| Teacher | 교사 님 | 敎師님 | Gyosa nim |

| Senior Student | 선배 | 先輩 | Seon bae |

| Black Belt | 단 | 段 | Dan |

| Student or Color Belt | 급 | 級 | Geup |

| Master level | 고단자 | 高段者 | Godanja |

| Other/Miscellaneous | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| English | Hangul | Hanja | Revised Romanization |

| School | 관 | 館 | Gwan (kwan) |

| Country Flag | 국기 | 國旗 | Guggi |

| Salute the flag | 국기 배례 | 國旗 拜禮 | Guggi baerye |

| Pay respect / bow | 경례 | 敬禮 | Gyeongnye |

| Moment of silence | 묵념 | 默念 | Mugnyeom |

| Sit down! | 앉아! | Anj-a! | |

| Thank you | 감사합니다 | 感謝합니다 | Gamsa habnida |

| Informal thank you | 고맙습니다 | Gomabseubnida | |

| You're welcome | 천만에요 | Cheonman-eyo | |

| Uniform | 도복 | 道服 | Dobok |

| Belt | 띠 | 帶 | Tti |

| Studio / School / Gym | 도장 | 道場 | Dojang |

| Test | 심사 | 審査 | Simsa |

| Self Defense | 호신술 | 護身術 | Hosinsul |

| Sparring (Kukkiwon/WT-style) | 겨루기 | Gyeorugi | |

| ...also Sparring (Chang Hon/ITF-style) | 맞서기 | Matseogi | |

| ...also Sparring | 대련 | 對練 | Daelyeon |

| Free sparring | 자유 대련 | 自由 對練 | Jayu daelyeon |

| Ground Sparring | 좌 대련 | 座 對練 | Jwa daelyeon |

| One step sparring | 일 수식 대련 | 一數式 對練 | il su sig daelyeon |

| Three step sparring | 삼 수식 대련 | 三數式 對練 | Sam su sig daelyeon |

| Board Breaking | 격파 | 擊破 | Gyeog pa |

Notable practitioners

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Namely Shotokan and Shudokan, which served as basis for styles practiced by the original nine Kwans.

- ^ Used by Chung Do Kwan and Moo Duk Kwan

- ^ Used by Yun Mu Kwan/Jidokwan and YMCA Kwon Bop Bu/Chang Moo Kwan

- ^ Was an early name of taekwondo before Choi Hong-hi managed to convince the organization to adopt the name taekwondo instead.

- ^ Tang Soo Do, Chung Do Kwan

References

[edit]- ^ Kang, Won Sik; Lee, Kyong Myung (1999). A Modern History of Taekwondo. Seoul: Pogyŏng Munhwasa. ISBN 978-89-358-0124-4.

- ^ "tae kwon do". OxfordDictionaries.com. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on January 9, 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ "tae kwon do". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ "tae kwon do". Cambridge English Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ "Flying Kicks: The Roots of Taekwondo and the Future of Martial Arts". Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Brief History of Taekwondo". Long Beach Press-Telegram. 2005. Archived from the original on 2011-08-15. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kang, Won Sik; Lee, Kyong Myung (1999). A Modern History of Taekwondo. Seoul: Pogyŏng Munhwasa. ISBN 978-89-358-0124-4.

- ^ "Korea officially designates taekwondo as nat'l martial art". The Korea Herald. 2 April 2018. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "World Taekwondo Federation (WTF) – Ji Ho Choi TaeKwonDo Institute". jhc-tkd.com. Retrieved 2025-01-15.

- ^ "Korea: Korean Martial Arts". www.koreaorbit.com. Archived from the original on 2019-06-20. Retrieved 2019-07-05.

- ^ Park, S. W. (1993): About the author. In H. H. Choi: Taekwon-Do: The Korean art of self-defence, 3rd ed. (Vol. 1, pp. 241–274). Mississauga: International Taekwon-Do Federation

- ^ Glen R. Morris. "The History of Taekwondo". Archived from the original on 2017-07-09. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ Cook, Doug (2006). "Chapter 3: The Formative Years of Taekwondo". Traditional Taekwondo: Core Techniques, History and Philosophy. Boston: YMAA Publication Center. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-59439-066-1.

- ^ Park, Cindy; Kim, Tae Yang (2016-06-12). "Historical Views on the Origins of Korea's Taekwondo". The International Journal of the History of Sport. 33 (9): 978–989. doi:10.1080/09523367.2016.1233867. ISSN 0952-3367. S2CID 151514066. Archived from the original on 2023-04-03. Retrieved 2020-03-21.

- ^ Moenig, Udo. "The Influence of Korean Nationalism on the Formational Process of T'aekwŏndo in South Korea". ao.81.2.10moe. Archived from the original on 2020-10-25. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

- ^ a b c d e f Gillis, Alex (2008). A Killing Art: The Untold History of Tae Kwon Do. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1550228250.

- ^ Lo, David. "Taekwon-do: A Broken Family?" (PDF). Thesis prepared for 4th dan granting requirements. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 1, 2017.

The President was amazed and asked General Choi what the new martial art is called. President Rhee was a nationalist, hated the Japanese and would not approve the soldiers practicing Japanese martial arts such as Tang Soo Do or Korean Karate. Someone said to the President that it was Tang Soo Do. 'No, it's T'aekkyon' the President countered. The president later instructed General Choi to teach the T'aekkyon martial art to more Korean soldiers.

- ^ テコンドーの歴史も2千年? 空手の親? 消された創始者(1/3). KoreaWorldTimes (in Japanese). 2021-07-23. Archived from the original on 2022-06-20. Retrieved 2021-09-22.

- ^ "General Choi, utilizing both his advanced education and Calligraphy skills that involved extensive knowledge of Chinese characters and language, searched for and later conceived of the new term Tae Kwon Do. This label more accurately reflected the shifting emphasis on the use of the legs for kicking". General Choi Taekwon-do Association (India) website. Archived from the original on 2019-06-05. Retrieved 2019-06-05.

- ^ "Interview with Nam Tae-Hi making it clear that Tae Kwon Do came from Korean Karate (also known as "Shotokan Karate," "Tang Soo Do" and "Kong Soo Do"). At a martial arts meeting in 1955, Choi presented a fictional argument connecting Taekwon-Do to Taekkyon, an old martial art". 2011. Archived from the original on 2019-07-01. Retrieved 2019-06-15.

- ^ Lo, David. "Nam and General Choi faced a dilemma as they could not teach the Koreans Karate and call it Taekkyeon. They needed a new name urgently but the President liked the name Taekkyon" (PDF). Thesis prepared for 4th dan granting requirements. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 1, 2017.

- ^ "World Taekwondo Federation changes name over 'negative connotations'". BBC Sport. 2017-06-24. Archived from the original on 2019-10-02. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ^ a b "Kukkiwon History". Kukkiwon.or.kr. Archived from the original on September 3, 2014. Retrieved September 7, 2014.

- ^ Williams, Bob (23 June 2010). "Taekwondo set to join 2018 Commonwealth Games after 'category two' classification". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 16 October 2010. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- ^ "WT Competition Rules". WorldTaekwondo.org. Retrieved September 7, 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Kim, Sang H. (2002). Martial Arts Instructors Desk Reference: A Complete Guide to Martial Arts Administration. Turtle Press. ASIN B001GIOGL4.

- ^ "Different styles of Taekwondo". ActiveSG. Archived from the original on 2021-01-20. Retrieved 2020-05-14.

- ^ a b c Choi, Hong Hi (1983). Encyclopedia of Taekwon-Do. International Taekwon-Do Federation. ASIN B008UAO292.

- ^ "ITF Austria". itf-tkd.org. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- ^ "ITF United Kingdom". Itf-administration.com. Archived from the original on August 7, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- ^ "ITF Spain". taekwondoitf.org. Archived from the original on January 23, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- ^ "ATA History". Ataon;ine.com. Archived from the original on September 28, 2014. Retrieved September 7, 2014.

- ^ "The Jhoon Rhee Story". Jhoonrhee.com. Archived from the original on February 18, 2015. Retrieved September 7, 2014.

- ^ "WTF History". Worldtaekwondofederation.net. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved September 7, 2014.

- ^ "Extreme Taekwondo". 30 June 2017.

- ^ "About Hupkwondo". 23 September 2016.

- ^ "Questions".

- ^ "Hanmoodo". 12 October 2023.

- ^ "Han Moo Do".

- ^ "What Is Han Mu Do".

- ^ "Han Mu Do". 26 May 2023.

- ^ "Teuk Gong Moo Sool" (PDF).

- ^ "Teuk Gong Moo Sool Germany".

- ^ "Martial Art - Gradings". British Taekwondo. 2024. Retrieved 2024-11-04.

- ^ Choi, H. H. (1993): Taekwon-Do: The Korean art of self-defence, 3rd ed. (Vol. 1, p. 122). Mississauga: International Taekwon-Do Federation.

- ^ Kukkiwon (2005). Kukkiwon Textbook. Seoul: Osung. ISBN 978-8973367504.

- ^ S. Benko, James. "Grand Master, Ph.D." The Tenants Of Tae Kwon Do. ITA Institute. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ "ITF More Culture". Archived from the original on September 11, 2014. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ "ITF Philosophy". Tkd.otf.org. Archived from the original on September 11, 2014. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ "WTF Philosophy". Worldtaekwondofederation.net. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ "Kukkiwon Philosophy". Kukkiwon.or.kr. Archived from the original on September 3, 2014. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ "ITF Theory of Power". Tkd.co.uk. Archived from the original on September 28, 2014. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ World Taekwondo Federation (2004). "Kyorugi rules". Rules. WorldTaekwondo.org. Archived from the original on 2007-07-02. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ a b c d e "WORLD TAEKWONDO FEDERATION COMPETITION RULES & INTERPRETATION" (PDF). World Taekwondo. October 1, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2017.

- ^ "Taekwondo Rules" (PDF). martialartsweaponstraining.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-03.(24 June 2017, p. 38)

- ^ Gomez, Brian (August 23, 2009). "New taekwondo scoring system reduces controversy". The Gazette. Archived from the original on 2013-12-02. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- ^ "British taekwondo chief says new judging system is far from flawless". morethanthegames.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010.

- ^ MARIA CHENG. "Is that a kick? Taekwondo fighters devise new ways to score". sandiegouniontribune.com. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2017-10-02. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ^ a b World Taekwondo Federation (Oct 7, 2010): Competition rules & interpretation[permanent dead link] (7 October 2010, pp. 31–32). Retrieved on 27 November 2010.

- ^ a b "WORLD TAEKWONDO FEDERATION POOMSAE COMPETITION RULES & INTERPRETATION" (PDF). World Taekwondo. October 1, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 2, 2017.

- ^ "itf-information.com". Archived from the original on 2012-06-13. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- ^ ITF World Junior & Senior Tournament Rules—Rules and Regulations

- ^ "30 Years of the Student National Taekwondo Championships". Archived from the original on 2 June 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ "AAU Taekwondo > Rules/Info > Rules Handbook > 2015 AAU Taekwondo Handbook Divided By Sections". Aautaekwondo.org. Archived from the original on 2015-06-19. Retrieved 2015-06-13.

- ^ "Main—World Taekwondo Federation". World Taekwondo Federation. Archived from the original on 2014-09-03. Retrieved 2016-04-30.

- ^ "information". Archived from the original on 15 February 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ "Paralympic Sports : Taekwondo|The Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games". The Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ Taekwondo World Qualification Tournament Outline, Archived February 19, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, page 3.

- ^ ITF TOURNAMENT RULES, pages 21–22.

External links

[edit]- Kukkiwon's Guide to Technical Terminology in Taekwondo Archived 2015-11-23 at the Wayback Machine